IN THE PAST 18 months, much of the world has relied on technology to connect with loved ones, complete projects with coworkers, and virtually attend school with classmates. But those changes can leave behind large numbers of people, particularly in the Blind and Deaf communities. Often, online communication tools lack subtitles or other inclusive features. And even with an interpreter hearing and deaf people alike can experience what’s known as the silent gap—an awkward delay as conversation is filtered through translation software and back again. “The Deaf community feels very proud of who they are and their culture, but historically they’ve been suppressed,” says Adam Munder, an engineer who is deaf. “Trying to interact with the hearing community can be challenging, and it’s time for technology to help bridge that gap.”

Assistive technologies have immense potential to open up the world to the Deaf community in new ways. “Ensuring accessibility is even more important during pandemics and other crises,” states a 2021 report by USAID. “New digital ecosystems can empower persons to access services they weren’t able to access previously, engage more effectively with others in their community, and pursue economic and education opportunities that might have been out of reach.”

“People have very different sets of capabilities,” says Lama Nachman, the director of Human and AI Systems Research Lab at Intel. “With assistive technologies, we’re focused on giving people what they need so they can thrive.”

Nachman should know. In 2011, she and a team of Intel engineers developed new communication software for Hawking, and the physicist made sure it was open-source, to lead to further advances. Since then, Nachman has spearheaded a team creating the kinds of innovations that will ensure no one is left behind.

“Technology can be a divide,” says Nachman, “but it can also bring people with different abilities together.”

Here are some of the forward-thinking, assistive technologies designed to support people of all abilities.

Using AI to Bridge Communities

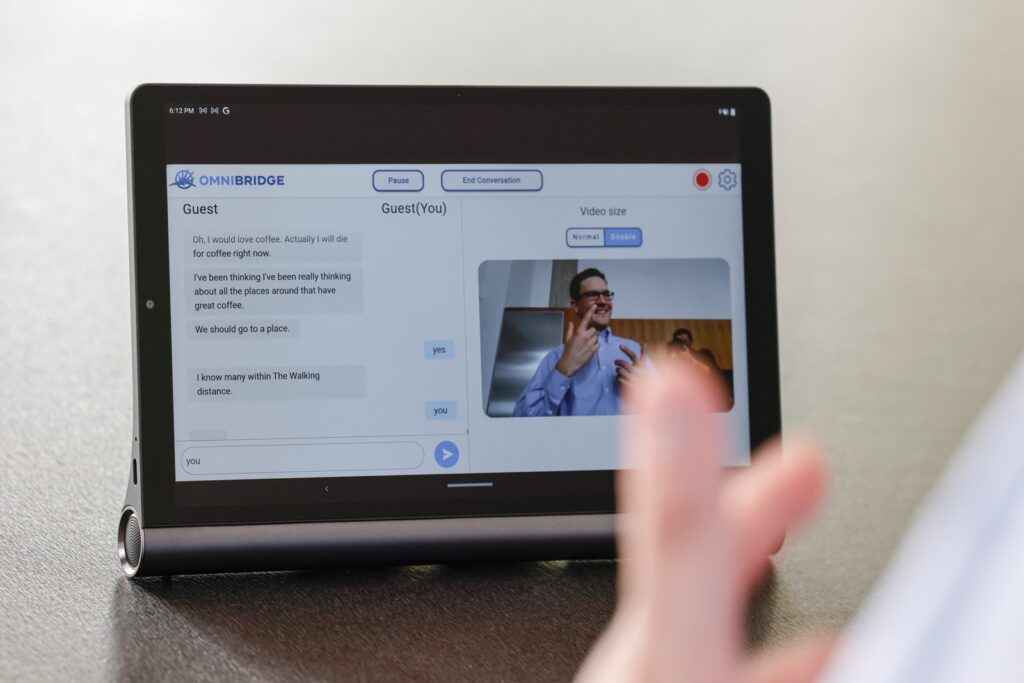

In 2015, Munder, then a development engineer at Intel, was asked to help create an app that could interpret sign language—a truly groundbreaking goal. Since he’d begun working at Intel, he’d had full-time access to an American Sign Language (ASL) interpreter, helping him communicate with colleagues on the job. Yet most of his peers in the Deaf and hard of hearing community didn’t have that kind of access, making everyday communication difficult for them. Outside work, Munder himself often found it challenging to express himself, reduced to scribbling messages when buying a cup of coffee or ordering a meal. The app he helped develop, known as OmniBridge, enables real-time ASL communication between the hearing and Deaf communities.

Codeveloped by Munder and Mariam Rahmani, a deep-learning software engineer, OmniBridge reimagines how these communities communicate with one another. Previously, deaf people needed human ASL interpreters to provide real-time translation, which is costly and often halting in a natural-flowing conversation. Also, interpreters need to be booked weeks in advance, which makes them a poor fit for unplanned, everyday occurrences like running errands. By contrast, OmniBridge facilitates instant communication between the Deaf and hearing worlds using technology that fits in the palm of the hand—a game-changing proposition. “I realized this technology could help make communication accessible to everyone,” Munder says, “and decided to jump in.”

To respond to a wide range of scenarios—be it an in-depth presentation or a quick comment to a coworker—Munder and the team envisioned software that could translate between voice and sign language in real time. The challenges were immense. First, there’s no real one-to-one correlation between ASL and English. Second, the human voice uses intonation and tone to convey meaning, and those subtleties would need to be understood and accurately translated into the correct sign. “A ton of work has been done in text-to-text translation, but not much on visual language to text,” Rahmani says. “It’s a much more complex task.”

The solution? Data. Drawing on cognitive computer programming technology, Munder and Rahmani invited people to sign, amassing more than one million hand-, face-, and body-sign samples. Then they designed the software to utilize RGB and 3D cameras, along with central and graphics processing units, to capture the wealth of detail a person conveys when they sign, then analyze it with AI and produce a written translation in English.

Currently, OmniBridge operates on a tabletop device that the team has developed, and it can only translate ASL into text. Munder is working to launch a prototype app later this year that can run on a tablet or smartphone, and ultimately wants the technology to enable real-time voice communication through avatars in numerous languages.

“We’re working to create a cloud-based solution that can run on any platform,” Munder says. “From the medical field to industrial manufacturing to education, this technology offers so many opportunities to enhance communication for everyone.”

Giving Voice to Everyone

Artificial intelligence is often thought of as strictly a computational phenomenon—a cutting-edge technology enabling computers to become “smart.” But Lama Nachman thinks of it differently. In her view, the greatest benefit of AI is its ability to augment human potential—to assist people in everyday life and support specific populations, like how OmniBridge is helping the Deaf community.

When Nachman began working with Stephen Hawking, for instance, the late physicist had perhaps the most recognizable computer-generated voice in history. For many, that robotic drawl had become his personality, and could be heard everywhere from TED talks to The Simpsons. Nachman and her partners at Intel developed the adaptive sensing system and the S/W platform that tracked Hawking’s limited facial movements and utilized these signals to enable him to communicate more effectively with the world. Hawking, of course, was a unique case—the Einstein of our generation—so it was understandable that he was given such customized support. But during their work to create a way for Hawking to communicate via his computer voice, both Hawking and Nachman knew the real goal was to create a system that could also be used by other people like him.

“He wanted an assistive technology to be part of his legacy,” says Nachman. “He understood there was a much larger need than just his.”

Powered by Intel hardware and software, the technology—which tracked Hawking’s subtle movements using the open-source Assistive Context-Aware Toolkit (ACAT)—is now leaps and bounds beyond where it was just a few years ago. Today, ACAT is not only able to track extremely subtle human movement—raising an eyebrow, moving an eye—but it’s able to learn over time and adapt to each individual user. By doing so, the system can be employed by a greater range of people but also operated more seamlessly. Nachman and her team at Intel are working to not only have the AI system generate responses, but also work collaboratively with the user to personalize these responses over time.

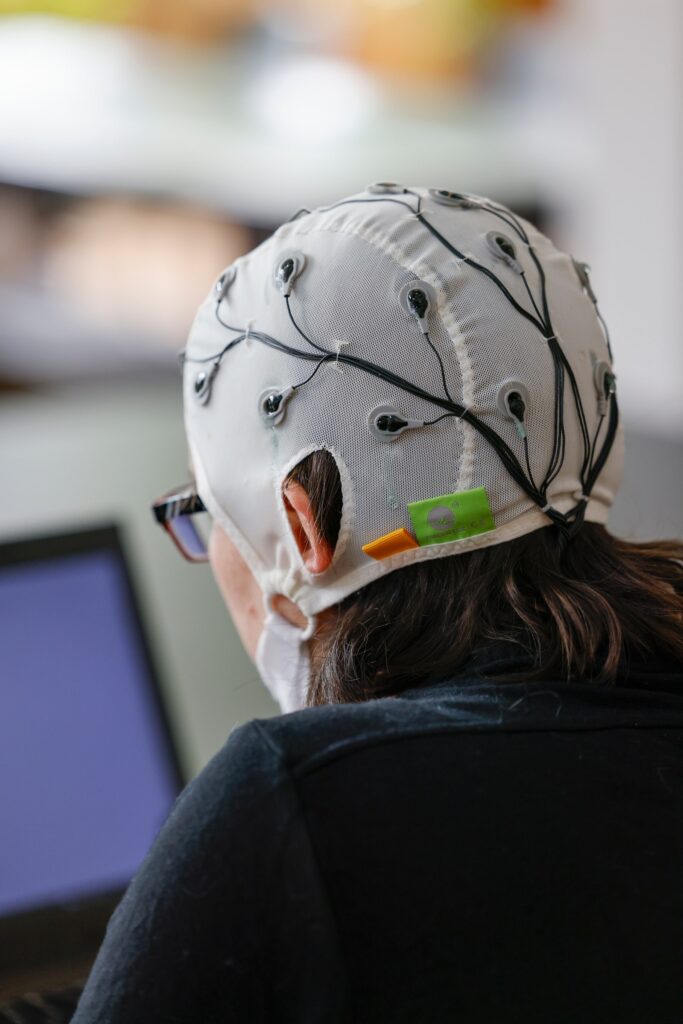

In the research lab that Nachman presides over, the team is also on the cusp of using brain waves to control a computer, and also doing it in a way that can scale to create the most positive impact for the greatest number of people.

“These systems tend to be crazy expensive,” says Nachman. “So if you want to achieve brain-computer interfaces, the real challenge is to do that by utilizing very cheap sensors, making it accessible to as many people as possible.”

The primary market for ACAT devices is people with motor neuron diseases like ALS. One day it may even be equipped with the banked voice of the individual using it, so that person can literally choose their own words as their condition progresses. In some instances, there may be no other way people with such diagnoses (like Hawking) can communicate.

“In the case of Stephen,” says Nachman, “he progressed to where he was only able to move his cheek. Other people can move their eyebrows. But if you’re not able to speak and can’t move any muscle, then we don’t have anything that we can utilize as a signal. The only thing that’s left is your brain waves.”

Nachman is helping to develop brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) that use a skullcap equipped with electrodes to monitor brain activity. As AI progresses, Nachman envisions a day when assistive technologies can perform all manner of tasks, from helping students in classrooms to aiding the elderly in their homes to supporting workers doing certain manual work. Already, there are prototypes developed for use in education and smart manufacturing. For Nachman, the goal is to amplify human potential and increase accessibility through technology.

“If you ask what drives me,” she says, “it’s how can we bring more equity into the world. With technology, we can change the dynamics that are very hard to solve any other way.”

Developing a Backpack That “Sees”

By many estimates, 285 million people worldwide are visually impaired, and many of today’s assistive solutions lack depth perception, which is necessary to navigate the world independently. Using Intel technology, AI developer Jagadish Mahendran and his team designed a voice-activated device that can help the wearer navigate traffic signs, crosswalks, approaching cars, and changes in elevation.

The system consists of a laptop outfitted with a concealed camera and tucked inside a small backpack, along with a waist pack containing a small battery pack. The camera scans the surrounding environment, assesses potential hazards, and relays that information to the wearer via a Bluetooth earpiece. Users can ask questions while they’re walking, like giving a “describe” command that prompts the system to identify nearby objects.

The computing power needed to accomplish this is massive, like cramming all of the technology in a self-driving car into a lunchbox. It’s accomplished with the power of Intel’s Movidius VPU, which enhances AI computing power at the edge, and the OpenVINO toolkit, which enables advanced algorithms to run on accelerator cards powered by multiple Movidius microchips.

This portable solution could transform the lives of people living with vision impairment, especially as the system is shared via open-source code and data sets. It’s just one of many groundbreaking innovations in assistive technology Intel and its partners are pioneering.

“The 10,000-foot view is this,” says Nachman. “We want to enable people to express themselves more naturally, to connect socially in ways they couldn’t before. Technology should support people in doing whatever they need to do.”

WIRED is where tomorrow is realized. It is the essential source of information and ideas that make sense of a world in constant transformation.

WIRED brand lab is the content and experience engine of wired, creating rich narratives and captivating experiences for partners that spark change and impact tomorrow. Together, we can change the future — influencing new ways of thinking, working, and communicating.